On intermediaries, mediators, (im)mobilities, and proximities #RaisingDissertation

It's not easy to see things in the middle, rather than looking down on them from above or up at them from below, or from left to right or right to left: try it, you'll see that everything changes. It's not easy to see the grass in things and in words" (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987).

Before you dive in, some key terms and concepts:

(Im)mobilities - as in effects, outcomes, events. Could be understood in terms of both resources and boundaries, as having the ability to move and as being forced to stay; as effects, outcomes, events that have political significance and relevance. (See also Pellegrino, 2011).

Proximity - as in relations. Could be understood in terms of nearness, farness, togetherness, and closeness to other actors; as physical, virtual, imaginative, and communicative travel of information. (See also Bissell, 2012).

Other key concepts: near-dwellers (Bissell, 2012); near-carriers (my term, 2015); ontology of belonging; institutional and peer surveillance (Jackson, 2012).

###

Somewhere in my literature review section might read this rumination on the everyday lives of young people, mostly Black and brown, living below the poverty line, and in-transition...

Intermediaries and Mediators

In Reassembling the Social (2005), Latour talks about the relationship between mediators and intermediaries as both human and non-human objects. Actor-Network Theory (ANT), describes an intermediary as a black box, or an object that can be viewed in terms of inputs and outputs without any knowledge of its internal workings. An intermediary, Latour writes, “transports meaning or force without transformation” (pg. 39). Mediators, unlike intermediaries, “transform, translate, distort, and modify the meaning or the elements they are supposed to carry” (pg. 39). In other words, objects that describe mediators transform meaning whereas objects that describe intermediaries do not transform.

But how do we decipher between mediators and intermediaries? For Latour, this is the first uncertainty in Actor-Network Theory; that is, whether or not objects behave as intermediaries or mediators, and it is also the source of all other uncertainties that follow.

Intermediaries and mediators lead researchers of associations into different territories. Intermediaries account for predictable outcomes, like for example, a large complex bureaucracy where objects perform repetitive and predictable tasks. Latour offers another example of an intermediary’s predictable behavior:

[A] highly sophisticated panel during an academic conference [that] may become a perfectly predictable and uneventful intermediary in rubber stamping a decision made elsewhere (pg. 39).

Mediators, unlike intermediaries are unpredictable. For example, a mediator may become complex and blow out in multiple directions like a banal conversation “where passions, opinions, and attitudes bifurcate at every turn” (pg. 39). Similar to Delueze’s rhizomatic concept, mediators point to the proliferations of objects and locates where these objects might connect to and expand toward. Mediators challenge us to follow flows rather than define containers.

ANT asks researchers of associations to treat all objects as mediators, as unpredictable and complex no matter how seemingly banal they may appear at first. This does not mean, however, that intermediaries cannot be studied nor recognized. In fact, as Latour suggests, intermediaries can become mediators and vice versa overtime. Rather than defining in advance what constitutes or makes up the social and cultural worlds we study, one approach to studying intermediaries and mediators, and their oscillating ways, is through description.

Enter: ethnography

I return now to an earlier discussion about intermediaries behaving in predictable ways. To further elaborate on the application of intermediaries in this research, I sought out other works aside from ANT and social theory where the concept of intermediaries was applied.

Yannakakis’ ethnohistorical study The Art of Being In-between (2008) explores indigenous resistance and colonial intermediaries of Sierra Norte of Oaxaca, a region of colonial Mexico. In Yannakakis work, we learn about native intermediaries, or those who “by virtue of their legitimacy among native peoples [helped to] administer colonial society” (pg. 2). Yannakakis’ study follows the trajectory of social rebellions and the rise of colonial intermediaries that became martyrs and some who were eventually declared saints centuries after their deaths. This ethnohistory provides another perspective about the ways intermediaries, in this case human actors, transport meaning from one group (natives) to another group (political elites). When citing Daniel Richter’s work on network theory and cultural brokers in the seventeenth-century (a concept synonymous with Yannakakis’ application of intermediaries), Yannakakis writes:

[Cultural brokers’] position in multiple networks and coalitions meant that they were both varyingly situated and not situated at all; they occupied an ‘intermediate position, one step removed from final responsibility in decision making [...] Participating in social networks from an intermediate position required not only considerable communicative skills but also a ‘tactical’1 sensibility (pg. 10).

Yannakakis applies the concept of intermediaries somewhat differently than Latour does in Reassembling. Throughout In-between, Yannakakis refers to intermediaries as bridges and brokers or those that “played a considerable role in connecting the colonial state to localities” (pg. 33). Yannakakis implies a bidirectional transfer of meaning (what goes through comes back) whereas Latour’s illustration of intermediaries depicts a unidirectional model of transfer (what goes in come out). However, where Yannakakis and Latour’s concept of intermediaries intersect is in how the transfer of meaning moves; that is, in predictable ways.

It is at this intersecting point in Latour and Yannakakis’ analyses that I enter into a discussion about the proximities (or relations) between human actors (near-dwellers) and non-human actors (near-carriers) as mediators and intermediaries, and how these proximities might constitute young peoples’ (im)mobilities.

Enter: a study of (im)mobilities and proximities in the lives of ‘disconnected’ youth

Through a mapping of (im)mobilities and proximities, I construct a visual representation of relations and events between research participants, technologies, institutions, as well as locate assemblages, entanglements, ruptures, flows, and discontinuities therein. Stripped of the abstract, this work essentially constitutes a story of everyday life for teens and young adults grappling with where and how to belong; when to stay, how to leave, when to log on, how to search, when to watch, and how to recognize when one is being surveilled. It is also a story about the politics of nearness and distance and how power relations are constantly reshaped between young people, key adults in their lives, unanticipated neighbors, police officers, technologies, and institutions.

My argument in this work goes without saying: Disconnected youth are far from disconnected. In fact, they dwell near, within, and among people, places, and things in foreseen and unexpected ways. For young people in transition from adolescence to adulthood, where they exist “in-between” jobs and schooling, their experiences also constitute paradoxical encounters. Where belonging on the block meets suspicion in the neighborhood, where animosity in the projects meets ambivalence in the city, where support at the cafe meets uncertainty at school, where curiosity online meets disinterest offline, where loss at home meets hope for the future. When blown a part these encounters reveal an apparatus of always-becoming, of always-in between.

###

Currently reading:

Bissell, D. (2012). Pointless mobilities: Rethinking proximity through the loops of neighbourhood. Mobilities, 8 (3), 349-367.

Fassin, D. (2015). Enforcing order: An ethnography of urban policing. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press.

Goffman, A. (2014). On the run: Fugitive life in an American city. New York, NY: Picador.

Lewis-McCoy, R.L. (2014). Inequality in the promised land: Race, resources, and suburban schooling. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Pellegrino, G. (2011). Studying (im)mobility through a politics of proximity. In G. Pellegrino, ed. The politics of proximity, 1-14. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Further reading:

Sheller, M. & Urry, J. (2012). Mobile technologies of the city. Routledge.

Urry, J. (2007). Mobilities. Polity Press.

Urry, J. (2002). Mobility and proximity. Sociology, 36 (2), 255-274.

Urry, J. (2000). Sociology beyond societies: Mobilities for the twenty-first century. Routledge.

Never stopped reading:

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

1 I apply Yannakakis’ definition here: “‘Tactics’ are the subtle, everyday actions undertaken by individuals to navigate, resist, and subvert authority” (pg. 33).

Simon Says: #ThatMomentWhen a research participant reminds you that you're a good person

A lot has been going on in my life. A lot of not-so-good things. Is Mercury retrograde over yet?

A lot has been going on in my life. A lot of not-so-good things. Is Mercury retrograde over yet?

While transcribing an interview from a conversation I had a few months ago with one of my research participants, I was reminded that my life still matters, and equally as important, that I *really* need to finish this dissertation. Mercury retrograde be damned.

The following is an excerpt from a conversation with a 19-year-old male from Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn. I'll call him Simon. This conversation occurred six months into data collection.

Tara: If this is the last time we ever speak, what is the one thing you want me to take away from this conversation?

Simon: That you have this charm to you. No real talk! Like you have a charm to you. Like, I be happy to see you everytime I see you.

Tara: It doesn’t have to be about me! That wasn't the point of me asking the question but that’s real sweet though.

Simon: Like you real cool. That’s the last thing I’d tell you! That you’re a very good person. That you’re very cool. That you’re charming.

Tara: Likewise. The feeling is mutual.

Simon: Thank you.

Tara: Do you have any questions for me?

Simon: When are you going to finish your dissertation?

#ThatMomentWhen social science research is cathartic. To be continued...

*UPDATED* On #McKinney, the Bayou, and Beyonce: Where Graphic Fiction Meets Graphic Reality Meets Formation

February 7, 2016: This post has been updated to include visual commentary on Beyonce's latest video and song, Formation.

Before going in, first read Zandria's post We Slay, Part I. I have nothing more profound or theoretical to add here. Instead I want to show the chronology of my own readings of racial violence of black bodies in the south as told through, by, and about black girls and women. As the post explains below, each semester I assign Bayou to my graduate students at Columbia. Eight months ago, I composed this post to illustrate the similarities between the McKinney pool party incident and the graphic novel's depiction of racial violence against black girls in the deep south. I conclude the original post stating: "The Bayou is an echo of the present." Bayou also tells the story of the future. Since June of last year, more black women have died in police custody as the Movement for Black Lives intensifies.

Yesterday, Beyonce debut her most political rendition of the state of black lives in the U.S. I could go on about the imagery and symbolism presented in the video, as so many others have already done. Instead, however, I'm going to incorporate a few images from the video that adds to my previous visual analysis in efforts to raise more questions about the relationship between time, space, racial violence, and black women and girls' bodies.

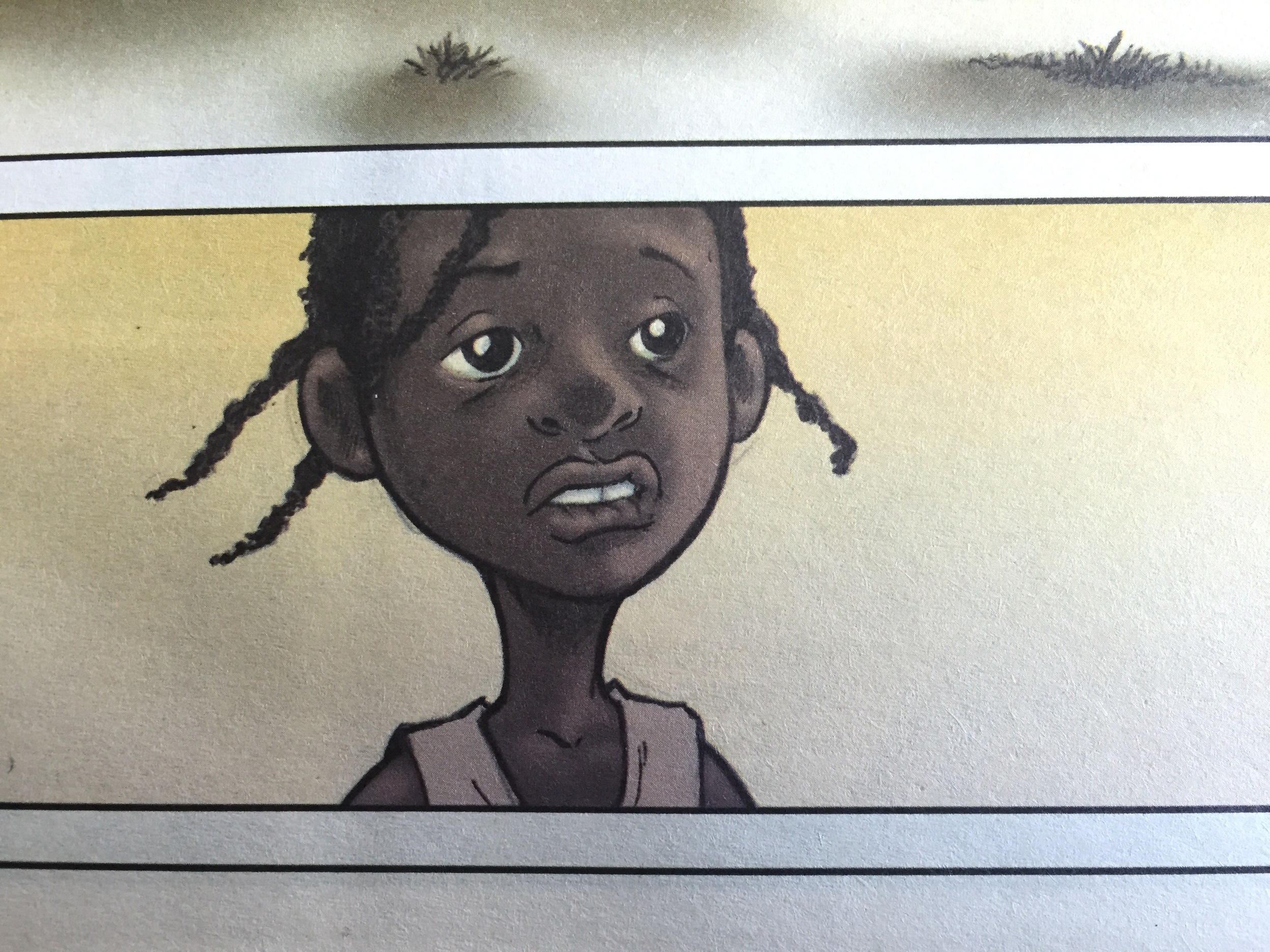

We see both Lee's body and Dajerria Becton's body on the ground, forced there by the hand of a white male police officer. Then we see Beyonce's body laid out atop of a New Orleans police vehicle sinking into the remaining waters left behind by hurricane Katrina. Is it a sacrifice--a death, a homage?

Then we see the two girls, Lee and Dajerria, nearly split images of one another; a picture of a black girl animated on paper next to herself in physical form, both superimposed through digital media. Lee and Dajerria are subjects of our gaze. Are they helpless--vulnerable? Then appears Blue Ivy, Beyonce's daughter, hands on hips, afro puffed. She's looking down smiling at our gaze. Is Blue redemption--a child of destiny, of what's to come of black girlhood in the future?

I present a chronology of visual images here, although it's clear to me that chronology and dimensionality cannot contain black existence. In fact, our bodies, experiences, myths, and deaths transcend time and space. Lee foreshadows Dajerria who flashbacks to Lee. Both represent a sacrificial moment; a death in present time. Lee is Dajerria is Beyonce is Blue. Redemption is embodied through our daughters.

The post below originally appeared on June 10, 2015.

###

This semester I'm teaching a course at Teachers College, Columbia University on Culture, Media, and Education. As part of the course, students are assigned to read a graphic novel of their choice and asked to provide a multimodal analysis of the text.

I participated in the assignment with my students this week and chose to read for the first time Jeremy Love's graphic novel Bayou (2009). (Side note to grad students: Reading short fiction is a refreshing escape from the daily grind of dissertating. I highly recommend). I was initially drawn to Bayou a few weeks ago in preparation for the course because of the novel's use of imagery to illustrate critical social commentary and historicize issues of racial violence in the south. I've always been drawn to bayou stories. Having spent a good portion of my young adult life living in the south, I find myself always deeply affected by stories of the bayou.

I didn't realize, however, the significance of Love's story until last week after learning about the McKinney pool party incident. A seemingly unfathomable scenario in which a white male police officer drags to the ground and publicly humiliates a Black teenage girl named Dajerria Becton in a majority-white gated community of north Texas.

The officer has since resigned from the police force. Yet, images and video of the incident continue to spread across the Internet, graphically displaying familiar tensions between Black youth (particularly Black girls) and police officers.

McKinney and the Bayou are eerily similar. Both take place in southern towns confronting issues of racial violence at the hands of white neighbors and police officers. The two narratives depict graphic imagery and accounts of towns that have been plagued by racial segregation. A microcosmic tale of a nation branded by its long and deeply troubling history of racism.

Despite its colorful and cartoonish animations, Bayou is far from a childish tale. The novel's images evoke racial trauma of years passed that even to this day reemerge by way of sharable content and online viral imagery. Bayou is a story of desperation, hopelessness, fear, triumph, and courage; an all-American anecdote about a little Black girl whose survival solely depended upon being brave while living in a racially divided town and country.

The Bayou is an echo of the present.

Blue Ivy Carter

Love's Bayou, Vol. 2 (2011) is also available for purchase.

[Bibliography] Towards an Anti-Racist Pedagogy in Ed Tech

Welcome CSA 2015! Feel free to peruse the bibliography for Towards and Anti-Racist Pedagogy in Educational Technology.

Welcome CSA 2015! Feel free to peruse the bibliography for Towards and Anti-Racist Pedagogy in Educational Technology.

Aslop, S. & Bencze, L. (2014). Activism! Toward a more radical science and technology education. In Bencze, L. and Alsop, S. (Eds.), Activist science and technology education (1-20). New York: Springer.

Bowen, G.M. (2014). Trajectories of socioscientific issues in new media: Looking into the future. In Bencze, L. and Alsop, S. (Eds.), Activist science and technology education (269-306). New York: Springer.

Dinerstein, J. (2006). Technology and its discontents: On the verge of the posthuman. American Quarterly, 58(3), 569-595.

Dewey, J. (1964a). Ethical principles underlying education. In Archambault, R.D. (Ed.), John Dewey on education (108-138). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Dewey, J. (1964b). My pedagogic creed. In Archambault, R.D. (Ed.), John Dewey on Education (427-439). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Fouche, R. (2012). From black inventors to one laptop per child: Exploring a racial politics of technology. In Nakamura, L. and Chow-White P.A. (Eds.), Race after the internet (61-83). New York: Routledge.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Fuhrman, S. (2015). Big data in education. Education Update.

Hedberg, J.G. (2011). Towards a disruptive pedagogy: changing classroom practice with technologies and digital content. Educational MEdia International, 48(1), 1-16.

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. New York: Routledge.

Hui Kyong Chun, W. (2012). Race and/as technology or how to do thing to race. In Nakamura, L. and Chow-White P.A. (Eds.), Race after the internet (38-60). New York: Routledge.

Marri, Anand R. (2007). Working with blinders on: A critical race theory content analysis of research on technology and social studies education. Multicultural Education & Technology Journal, 1(3), 144-161.

Milberry, K. (2014). #OccupyTech. In Bencze, L. and Alsop, S. (Eds.), Activist science and technology education (255-268). New York: Springer.

Patton, D.U., Eschmann, R.D., Butler, D.A. (2013). Internet banging: New trends in social media, gang violence, masculinity and hip hop. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(5), 54-59.

Rodriguez, A. (2014). A critical pedagogy for STEM education. In Bencze, L. and Alsop, S. (Eds.), Activist science and technology education (55-66). New York: Springer.

Roth, W.M. (2014). From-within-the-event: A post-constructivist perspective on activism, ethics, and science education. In Bencze, L. and Alsop, S. (Eds.), Activist science and technology education (237-254). New York: Springer.

Sanchez-Casal, S. and Macdonald, A. A. (2002). Feminist reflections on the pedagogical relevance of identity. In Sanchez-Casal, S. and Macdonald, A. A. (Eds.), Twenty-first-century feminist classrooms: Pedagogies of identity and difference (1-28). New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Fieldnotes 2: "In New York City, you have to make your own space"

The following are excerpts from my fieldnotes describing a recent site visit. The names have been changed to protect privacy.

The following are excerpts from my fieldnotes describing a recent site visit. The names have been changed to protect privacy.

Excerpt 1

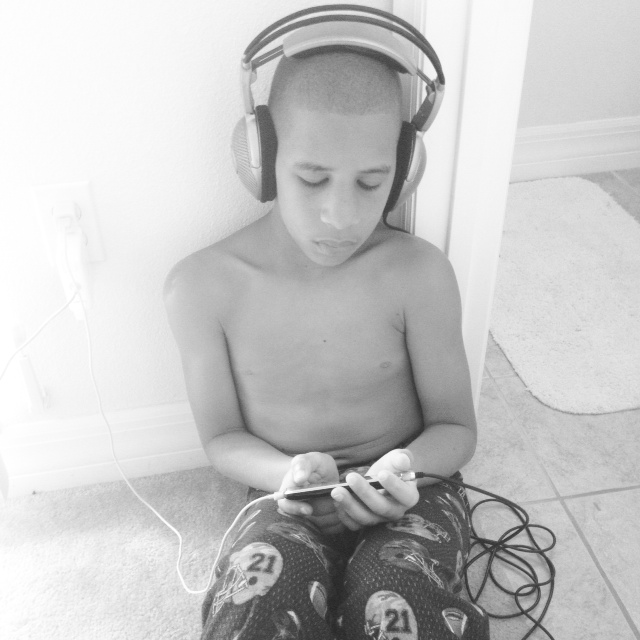

Roughly 45-minutes into the three hour visit, I noticed something interesting happening. This wasn’t anything I hadn't seen or read about before. It was certainly an instance that I’ve witness emerge inside and outside of classroom spaces, at public events, and around the dinner table. As Chad, a frequent customer at the cafe, talked to me, I noticed behind the counter that Ethan, Ben, and another young man who worked there were all hunched over their cell phones. iPhones, to be exact.

“Yo, you didn’t tag me, son!” Ethan said to Ben. There weren’t any customers in the cafe at this point. Ethan and Ben, while sitting behind the counter, were looking at their phones toggling through Instagram photos.

“Yo, she is ugly, son!” Ethan said to Ben, laughing. Chad looked up from our conversation and asked who they were looking at.

“That’s wifey.” Ethan responded looking at the iPhone screen.

“His wifey is ugly? How’s that?” Chad asked.

“No, no,” Ethan replied, “We looking at another picture now.”

If the cafe was a gendered space, it couldn’t be anymore masculinist than it was at this particular moment. This is what being in a barbershop must feel like, I thought to myself. I was the only woman in the space but that didn’t stop Ethan, Ben, and Chad from exchanging banter about pics of girls and women they gawked at on Instagram. These were light moments between Ethan, Ben, and Chad. I didn’t interject.

Later in the conversation, I asked Ethan and Ben if they were on Twitter.

“Nah,” replied Ethan.

They preferred Instagram along with a new Instagram-like application called Shots.

“Twitter is for females.” Chad interjected. “It’s gossipy, you know?”

“And Instagram isn’t?” I responded. (I had to.)

“Instagram is messy, but not gossipy like Twitter.” Chad replied.

We spent the next fifteen minutes talking about Twitter, Instagram, and then Facebook--which everyone, even me, seemed to agree was wack.

“People break up over Facebook, yo!” Ethan announced.

He told me about the time his girlfriend saw that he liked another girl’s picture on Instagram.

“I was liking this girl's pic to get more followers. It’s like promotion.” He said.

When Ethan's girlfriend found out that he was liking other girl's pictures on Instagram, she ended the relationship.

“I didn’t even do nothing!” He said.

Ben, who at this point I’ve dubbed the quiet one (relative to Ethan), asked if I was on Instagram. I told him I was, but that my account is private. I told him that I’m more active on Twitter. It’s where I get my news.

“Twitter used to be hot back in the day when it first came out, but not anymore.” Ethan said.

In many ways, I agreed with him. Twitter is a much more difficult space to navigate these days than in previous years. But perhaps so is social media in general.

Ethan showed me a picture of him on Instagram when he was 15-years-old. Ben posted the photo but forgot to tag Ethan. If Ethan wasn’t sitting directly next to Ben while they were scrolling through pictures, he probably wouldn't have noticed that Ben didn’t tag him.

“Can I take a picture of you guys while you're looking at your phones?” I asked.

Ethan eyes lit up. “Yes! You gonna put it on Instagram?”

I told Ethan and Ben that I would never post their pictures on Instagram. I also told them that the photos I was taking throughout the day were only going to be used for research.

But Ethan persisted. “You can put [the pic] on Instagram if you want.”

I didn't. Instead, I texted the photos to Ethan's cell phone.

These young men, although labeled disconnected at one point in their lives, were anything but. They moved about in the physical space of the cafe. They also moved about in the virtual spaces of social media. Their bodies, identities, and constructs moved fluidly across time and space. Sociality manifested as mobilities within and among physical, virtual, online, and offline spaces (or places?). These movements, constructs, activities, or whatever you call it were indicative of two very connected and co-present people.

Ethan and Ben's iPhones played significant roles in how connection was established and maintained. These objects, in other words, sustained connection. They also remained in Ethan and Ben's pockets the entire time while they served customers coffee and food.

Yet, Ethan and Ben clearly chose when and where to connect. While they sat in the physical space of the cafe--a constant, sustaining, and perhaps even safe place--the virtual spaces they participated in via their iPhones were not on equal footing. To Ethan and Ben, the spaces that constitute social media held different meanings about their interactions with other people.

Excerpt 2

Later on that day, Patrick, a white guy and regular customer arrived. He playfully argued with Ethan saying that Samsung makes better phones and electronics than does Apple. Ethan wasn’t hearing it though. He, and I too, pointed out how the Apple brand is much more sophisticated than Samsung.

"But, then again," I interjected, “neither Apple nor Samsung are paying my bills so for me it’s not that serious.” I said this while pulling out my iPad Air to check my email.

The banter continued. It was a lovely indication and reminder that there was community here, and it was alive, emerging, and always-becoming.

The topic of conversation shifted. I found out that Patrick was once a middle school teacher. He lived in the neighborhood. Patrick talked about once working in rural North Carolina. He loved the students but hated the parents. He chose to quit teaching once he realized he wasn’t being supported.

Patrick then talked about how it was too expensive to live in Bed-Stuy.

“You can’t find a studio in this neighborhood for less than $1100,” he said.

“Shit, if that!” Chad interjected.

Patrick continued, “The Hassidics are buying up the blocks around here. Then, you know what they do? They rent out rooms. Not apartments. Rooms! You end up living in a shoebox for thousands of dollars.”

“Yeah, that’s pretty crazy” I replied.

“In New York City, you have to make your own space,” Patrick said.

Space, an enigmatic concept, seems to facilitate and impede connection all at once, doesn't it? How then do we make spaces when, in our own lives, space is so obviously scarce, devalued, contested, and always-becoming?