Pilot Study Bibliography: Participatory Design, CI Youth, & Mobile Tech

The following is an ever growing alphabetized bibliography (you're welcome) of my current doctoral research involving participatory design, court-involved youth, and mobile technology.

The following is an ever growing alphabetized bibliography (you're welcome) of my current doctoral research involving participatory design, court-involved youth, and mobile technology.

Update #2: 4/19/15 - Welcome #AERA15! Feel free to peruse the pilot study bib below. Keep in touch on Twitter @taralconley!

Update #1: 9/25/14 - Welcome #ONA14! Feel free to peruse the bib below. Keep in touch on Twitter @taralconley!

Welcome #RLR2014 participants! Please take a moment to fill out a very brief questionnaire about Monday's presentation. Your feedback is greatly appreciated! Click here to take survey

References

Abu-Lugod, L. (1990). Can there be a feminist ethnography? Women and Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory, 5(1), 7-27.

Anzaldúa, G.A. (1987). Borderlands/la frontera: The new mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute.

Anzaldúa, G.A. (2002). now let us shift…the path of conocimiento…inner work, public acts. this bridge we call home: radical visions for transformation. In Eds. G.A. Anzaldúa and A. Keating (Eds.), (pp. 540-578). New York, NY: Routledge.

Anzaldúa, G.A. (2002). (Un)natural bridges, (un)safe spaces. this bridge we call home: radical visions for transformation. In Eds. G.A. Anzaldúa and A. Keating (Eds.), (pp. 1-5). New York, NY: Routledge.

Asaro, P.M. (2000). Transforming society by transforming technology: the science and politics of participatory design. Accounting Management and Information Technologies, 10, 257-290.

Bernard, R. (2006). Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Lanham, Maryland: AltaMira Press.

Bohannon, L. (1954). Return to laughter. New York, NY: Harper.

boyd, d. (2008). Friendship. In I. Mizuko, S. Baumer, M. Bittanti, d. boyd, R. Cody, B. Herr, H. A. Horst, P. G. Lange, D. Mahendran, K. Martinez, C.J. Pascoe, D. Perkel, L. Robinson, C. Sims, and L. Tripp. Hanging Out, Messing Around, Geeking Out: Living and Learning with New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bustamante Navarro, R. (2013). Participatory design Guide for Mental Health Promotion in prisons. Revista española de sanidad penitenciaria, 15(2), 44-53.

Capetillo-Ponce, J. (2006). Exploring Gloria Anzaldúa's methodology in Borderlands/La frontera-the new mestiza. Human Architecture, 4, 87-94.

Center for an Urban Future. (2009). A need for correction: Reforming New York’s juvenile justice system, 18.

Communities United for Policing Reform. (2012). About the Community Safety Act. Retrieved from http://changethenypd.org/about-community-safety-act. Accessed on Aug. 5, 2013.

De Souza e Silva, Adriana. (2006). Interfaces of hybrid spaces. In A.P. Kawoori & N. Arceneaux (Eds.), The cell phone reader: Essays in social transformation (pp. 19-44). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Dinerstein, J. (2006). Technology and its discontents: On the verge of the posthuman. American Quarterly. 58(3), 569-595. DOI: 10.1353/aq.2006.0056

Faber, J., Bensky, L., & Alpert, L. (2009). The long road home: A study of children stranded in New York City foster care. Children’s Rights. 1-230.

Fitch, D. (2012). Youth in foster care and social media: A framework for developing guidelines. Journal of Technology in Human Services. 30(2), 94-108, DOI: 10.1080/15228835.2012.700854

Flango, V.E. & Sydow, N. (2011). Educational well-being: Court outcome measures for children in foster care. Future Trends in State Courts: A Special Focus on Access to Justice. Report.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: The Continuum International Publishing Group, Inc.

Gailey, C.W. (1998). Feminist methods. In H.R. Bernard (Ed.), Handbook of Methods in Cultural Anthropology (pp. 203-234). Walnut Creek, California: Alta Mira Press.

Goodman, D.J. (2013). Bloomberg vetoes measures for police monitor and lawsuits. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/24/nyregion/bloomberg-vetoes-measures-for-police-monitor-and-lawsuits.html?_r=0. Accessed on Aug. 4, 2013.

Gordon, J. (2006). The cell phone: An artifact of popular culture and a tool of the public space. In A.P. Kawoori & N. Arceneaux (Eds.), The cell phone reader: Essays in social transformation (pp. 45-60). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Haraway, D. (1991). Simians, cyborgs and women: The reinvention of nature. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hicks, S., Duran, B., P.H., Wallerstein, N., P.H., Avila, M., P.H., Belone, L., Lucero, J., & Hat, E. W. (2012). Evaluating community-based participatory research to improve community-partnered science and community health. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 6(3), 289-99.

Holone, H., & Herstad, J. (2013). Three tensions in participatory design for inclusion. Proceedings from CHI 2013: Changing Perspectives. Paris, France.

Jenkins, H. (2009). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture: Media education for the 21st century [White paper]. Retrieved from digitallearning.macfound.org/atf/.../JENKINS_WHITE_PAPER.PDF

Latour, B. (1991). We have never been modern. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Lave, J. (1991). Situating learning in communities of practice. In L. Resnick & S. Teasley (Eds.), Perspectives on socially shared cognition (pp. 63-82). Washington, DC: APA.

Leone, P. & Weinberg, L. (2010). Addressing the unmet educational needs of children and youth in the juvenile justice and child welfare systems. Center for Juvenile Justice Reform. Georgetown University. Report.

Levinson, P. (2004). The little big blender: How the cellphone integrates the digital and the physical, everywhere. In A.P. Kawoori & N. Arceneaux (Eds.), The cell phone reader: Essays in social transformation (pp. 9-18). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Light, A., and Luckin, R. (2008). Designing for social justice: People, technology, and learning. Futurelab.

Lounsbury, K., Mitchell, K.J., and Finkelhor, D. (2011). The true prevalence of “sexting”. Crimes Against Children Research Center. University of New Hampshire.

Lustria, M.L.A., Kazmer, M.M., Glueckauf, R.L., Hawkins, H.P., Randeree, E., Rosario, I.B., McLaughlin, C., Redmond, S. (2013). Participatory design of a health informatics system for rural health practitioners and disadvantaged women. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 61(11), 2243-2255.

McAllister, J. (2008). Overcoming system failure to help youth find and sustain positive relationships. Fostering Perspectives, 13(1).

McPherson, T. (2012). U.S. operating systems at mid-century: The intertwining of race and UNIX. In L. Nakamura & P. Chow-White (Eds.), Race after the internet (pp. 21-37). New York, NY: Routledge.

Muller, M. J. & A. Druin. (2002). Participatory design: The third space in HCI. In J. A. Jacko and A. Sears (Eds.), The Human Computer Interaction Handbook: Fundamentals, Evolving Technologies and Emerging Applications (pp. 1051–1068). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

New York City Family Court. (2010). New York City family court annual report. Report.

NYC.gov. (2013). Mayor Bloomberg signs legislation merging the Department of Juvenile Justice into the Administration for Children’s Services. Retrieved from http://www.nyc.gov/html/acs/html/pr_archives/pr10_12_07.shtml

Peterson, S.B. (2010). Examining the referral stage for mentoring high-risk youth in six different juvenile justice settings. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Report.

Pollock, M., & Amaechi, U. (2013). Texting as a channel for personalized youth support: Participatory design research by city youth and teachers. Learning, Media, and Technology, 32(8), 128-144.

Priest, D. (2013, Aug. 8). Piercing the confusion around NSA’s phone surveillance program. The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://articles.washingtonpost.com/2013-08-08/world/41198127_1_phone-records-phone-surveillance-program-metadata-program

Rainie, L. & Wellman, B. (2012). Networked: The new social operating system. Boston, MA: The MIT Press.

Ringrose, J., Gill, R., Livingstone, S., Harvey, L. (2012). A qualitative study on children, young people, and ‘sexting’. NSPCC.

Ruderman, W. (2013). To stem juvenile robberies, police trail youths before the crime. The New York Times. Accessed on Aug. 4, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/04/nyregion/to-stem-juvenile-robberies-police-trail-youths-before-the-crime.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0. Accessed on Aug. 4, 2013.

Scheindlin, S.A. (2013) Case 1:08-cv-01034-SAS-HBP Document 373. New York, New York.

Simmel, G. (1903). The metropolis and mental life. The sociology of Georg Simmel, ed. Kurt Wolff.

Glencoe, IL: Free Press, 1950), 409-424. Social Services Information Systems (SSIS) (2004). Federal definitions of foster care and related terms. U.S. Government Printing Office.

Spinuzzi, C. (2006). The methodology of participatory design. Technical Communication, 52(2), 163-174.

Stald, G. (2008). Mobile identity: Youth, identity, and mobile communication media. In D. Buckingham (Ed.), Youth, Identity, and Digital Media (pp. 143-164). The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. doi: 10.1162/dmal.9780262524834.143

Task Force on Transforming Juvenile Justice (TFTJJ). (2009). Charting a new course: A blueprint for transforming juvenile justice in New York state. Report.

Telerivet. (2012) www.telerivet.com

The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. (2008). Sex and tech: Results from a survey of teens and young adults. Washington, DC.

The New York City Administration for Children’s Services. (May 2013). Flash Report. New York, New York.

The New York City Administration for Children’s Services. (July 2013). Flash Report. New York, New York.

Triantafyllakos, G., Palaigeorgiou, G., & Tsoukalas, I.A. (2010). Fictional characters in participatory design sessions: Introducing the “design alter egos” technique. Interacting with Computers, 22(3) 165-175.

Visweswaran, K. (1994). Defining feminist ethnography. In K. Visweswaran (Ed.), Fictions of Feminist Ethnography (pp. 17-39). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Wheately, M. & Frieze, D. (2006). Using emergence to take social innovations to scale. Margaret Wheately. Retrieved from http://www.margaretwheatley.com/articles/emergence.html. Accessed on March 12, 2013.

Winner, L. (1980). Do artifacts have politics? Daedalus, 109(1), 121–136.

Yamauchi, Y. (2012). Participatory design. In T. Ishida (Ed.), Field Informatics (pp. 123-138). Welwyn, United Kingdom: Springer.

Additional References

Cannon, A., Aborn, R., Bennett, J., and Segal, C.P. (2010). Citizens crime commission of New York City: Guide to juvenile justice in New York City. Citizens Crime Commission of New York City, Inc.

Checkoway, B. (2011). What is youth participation? Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 340-345.

Empire State Coalition of Youth and Family Services. (2011). The New York City association of homeless and street-involved youth organizations: State of the city's homeless report.The New York City Association of Homeless and Street-Involved Youth organization.

European-American Collaborative Challenging Whiteness. (2005). Critical humility in transformative learning when self-identity is at stake. Sixth International Transformative Learning Conference, Michigan State University, Oct. 6-9.

General Assembly (1989). Conventions on the rights of the child. Retrieved from http://www.crin.org/docs/resources/treaties/uncrc.asp#Twelve

Lewin, K (1946). Action research and minority problems. The Journal of Social Issues, 2(4), 34-46.

New York State Office of Children and Family Services. (2010). Monitoring and analysis profiles with selected trend data: 2006-2010.

Oakes, J., Rogers, J., & Lipton, M. (2009). Learning power: Organizing for education and justice. John Dewey Lecture. New York: Teachers College Press.

Pateman, C. (1970). Participation and democratic theory. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Rousseau, J.J. (1968). The Social Contract, Cranston, M. (trans), Penguin Books.

Schuler, D. & Namioka, A. (1993). Participatory design: Principles and practices. CRC Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Schultz, K. (2010). After the blackbird whistles: Listening to silences in classrooms. Teachers College Record, 112(11), 2833-2849.

The New York City Administration for Children’s Services. (Sept. 2013). Flash Report. New York, New York.

U.S. Census Bureau, 2010 and 2000 Census Public Law 94-171 Files and 1990 STF1

Walker, A. (2011). When gangs were white: Race, rights, and youth crime in New York City, 1954-1954. Saint Louis University School of Law, 55(1369), 1369-1379).

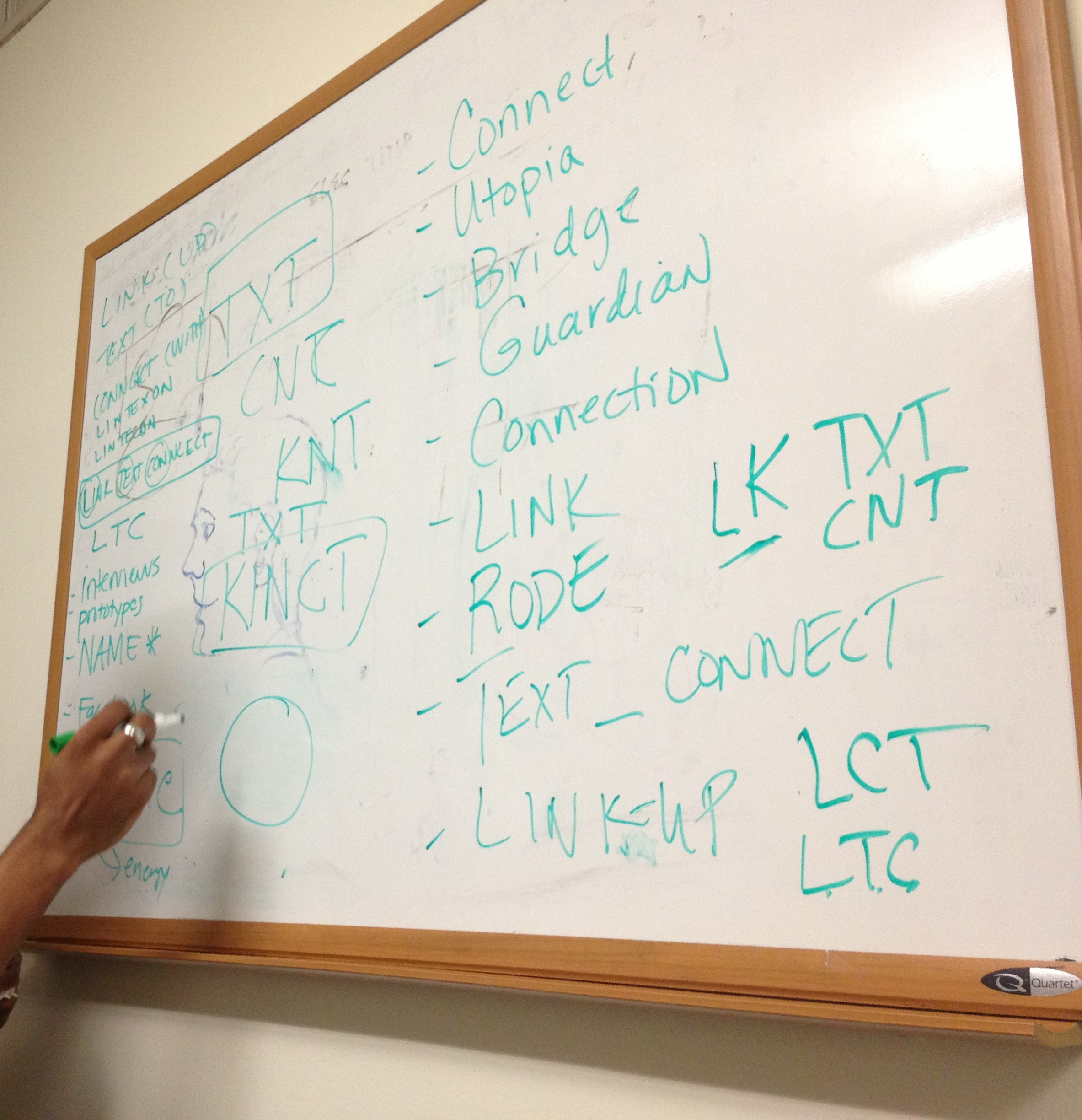

Excerpt from my current research on #PD #mobile #youth #justice

(Photo by Tara L. Conley)

The following is an excerpt from an article draft I'm currently working on about participatory design, mobile text messaging service, and court-involved youth:

During the summer of 2013 amid a controversial mayoral race in New York City[1], mayor Michael Bloomberg vetoed legislation that, in part, would create an independent inspector general to oversee the New York City Police Department (Goodman; 2013) and would allow for an expansive definition of individual identity categories under the current law. The four bills, together named the Community Safety Act (Communities United for Policing Reform; 2012), were brought forth by City Council as a result of a legal policing practice called Stop-and-Frisk. This policing practice allows New York City police officers to stop, question, and frisk citizens under reasonable suspicion of criminal activity.

While New York City residents were at odds over mayoral candidates and policing practices, young people involved in both foster care and juvenile justice systems were developing and designing a free text messaging service that would support court-involved youth in New York City to access resources and services using their cell phones. Three months before Bloomberg vetoed the Community Safety Act in New York City and while the city’s political sexting [2] scandal garnered national attention, several young people and I were discussing ways mobile technology could be used to help court-involved youth stay connected to their communities. Unaware about the extent to which Stop-and-Frisk and other safety concerns affected young people, I brought forth the idea of a text messaging platform that would primarily function as means of connecting court-involved youth to educational resources such as tutoring services and neighborhood jobs. At the time, the purpose of the platform was to create an intimate and anonymous means for young people involved in both foster care and juvenile justice systems to seek out resources beyond the institutions to which they were bound. Cell phones, I thought, would be the easiest and most comfortable way to facilitate a connection between young people and their communities.

However, the more I talked with young people, the more I understood that connecting to their communities not only meant accessing educational resources, job listings, and intervention services like hotlines, it also meant seeing the mobile device itself as a documentation tool and mobile companion for young people as they navigate the terrain of constant surveillance (Ruderman; 2013) and unstable home lives, all while trying to grasp for themselves a sense of belonging amid a psychological battlefield of metropolis dwelling [3].

Notes

[1] While running for mayor of New York City, former US congressman Anthony Weiner was involved in a national sex scandal, of which he admitted to sending sexually explicit text messages to several young women. Weiner’s indiscretions was the focal point of the NYC mayoral race and national news.

[2] Sexting is a term that describes the act of sending and receiving sexually explicit messages usually over a mobile device. The terms “sex” and “texting” began to appear in survey literature as early as 2008. Shortly thereafter the term “sexting” (a word formed by combining “sex” and “texting”) began to appear widely in academic studies and mainstream media and news (see The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy; 2008; Lounsbury, et. al.; 2011, and Ringrose, et. al., 2012).

[3] Simmel (1903) writes about the ancient polis, or city-state, as it relates to the small town. Both the city and town share an anxiety of “incessant threat” by outsiders, or enemies seen as outsiders. Simmel argues that because of this collective anxiety the environment becomes “an atmosphere of tension in which the weaker were held down and the stronger were impelled to the most passionate type of self-protection” (pg. 16). One might argue that the conditions young people experience in the city, particularly in New York City is symptomatic of an anxiety-ridden atmosphere.

References

Communities United for Policing Reform. (2012). About the Community Safety Act. Accessed on Aug. 5, 2013. Retrieved from http://changethenypd.org/about-community-safety-act

Goodman, D.J. (2013). Bloomberg vetoes measures for police monitor and lawsuits. The New York Times. Accessed on Aug. 4, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/24/nyregion/bloomberg-vetoes-measures-for-police-monitor-and-lawsuits.html?_r=0

Lounsbury, K., Mitchell, K.J., and Finkelhor, D. (2011). The true prevalence of “sexting”. Crimes Against Children Research Center. https://www.unh.edu/ccrc/pdf/Sexting%20Fact%20Sheet%204_29_11.pdf

Ringrose, J., Gill, R., Livingstone, S., Harvey, L. (2012). A qualitative study on children, young people, and ‘sexting’. NSPCC. http://www.nspcc.org.uk/Inform/resourcesforprofessionals/sexualabuse/sexting-research-report_wdf89269.pdf

Ruderman, W. (2013). To stem juvenile robberies, police trail youths before the crime. The New York Times. Accessed on Aug. 4, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/04/nyregion/to-stem-juvenile-robberies-police-trail-youths-before-the-crime.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

Simmel, G. (1903). “The Metropolis and Mental Life” translated and published in The Sociology of Georg Simmel, ed. Kurt Wolff (Glencoe, IL: Free Press, 1950), 409-424.

The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. (2008). http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/sextech/pdf/sextech_summary.pdf

Court-involved youth and social meanings of mobile phones

photo by Tara L. Conley

“The mobile is the glue that holds together various nodes in these social networks: it serves as the predominant personal tool for the coordination of everyday life, for updating oneself on social relations, and for the collective sharing of experiences. It is therefore the mediator of meanings and emotions that may be extremely important in the ongoing formation of young people’s identities” (Stald; 2008, pg. 161).

"Dependency Court involved youth rarely have access to a computer or cell phone, and even when they do, it is often only for a short period of time" (Peterson; 2010, pg. 7).

The following is a conversation about cell phones between me and young people involved in foster care and juvenile justice systems. This excerpt is part of ongoing research. Please do not republish.

Tara: I have a question. You all have cell phones, right? And they’re reliable? Do young people [who are court-involved] have cell phones? Do they have data plans? Do they have Smartphones? Do they have flip phones?

Male 1: Some of them have flip phones. Some of them have Smartphones. There are some of them who are scared to pull out their flip phones because...

Female 1: They may get picked on.

Male 1: Exactly!

Tara: They might what?

Female 1: Picked on.

Tara: Picked on? Really?

Male 1: Yes!

Tara: Because they have a flip phone and not a Smartphone?

Male 1: Yes!

Tara: That’s horrible.

Male 1: Kids are vindictive.

Male 2: If you still got a Blackberry you might get picked on.

Female 1: I have a Blackberry. How does that make me less of a person? Because I don’t have an upgraded phone like you?

Male 1: I like it! My Blackberry. I like it more because it’s more of a useful phone than the iPhone and the Galaxy.

Female 1: But you know what? I also think it’s the media that portrays it that way. Like we need it.

Male 1: Of course.

Female 1: It’s like water. Our tap water gets checked everyday to make sure it’s safe for our bodies, but [bottled water] might not get checked as much, but they make it seem like we need it more.

Male 1: But see, if you want to talk about that, that’s on a whole other level. That’s propaganda!

Female 1: But they make it seem like we need this special water.

Male 1: Yeah! They do that with everything! It’s how the government makes money off of the foolish.

Male 2: But then there’s a lot of girls who be like, ‘Oh, if you don’t have an iPhone 5, you’re not popular.’

[Laughing]

Male 1: Yup.

Male 2: The kids get into stuff like that you know. So, I mean there are some kids who don’t have a phone...

Tara: You have an iPhone?

Male 1: Yeah, the 5.

Tara: You have an iPhone?

Female 2: No, the Galaxy Exhibit.

Tara: But they’re all Smartphones?

Male 1, Male 2, Female 1: Yeah.

Male 1: Most of the time, look, it’s hard as hell right now to find a flip phone.

[Laughing]

Male 1: I’m not even going to lie, if you got a flip phone, I’m probably gonna laugh.

[Laughing]

References

Peterson, S. B. (2010). Dependency court and mentoring: The referral stage. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Stald, G. (2008). Mobile identity: Youth, identity, and mobile communication media. Youth, Identity, and Digital Media. Edited by David Buckingham. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning. pp. 143–164. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

In the future, we will be the Internet

Excerpt from Azuka Nzegwu's dissertation "The Conduit and Whirlpooling: A New Theory of Knowledge Constitution and Dispersion" (2010)

"[Philip Emeagwali's] prediction is that in one hundred years, people will become nodes, which are connective dots, on the Internet. He describes a scenario fifty years from now in which the body of one’s grandchild will be registered as, and become a node on, the Internet. As a node, the child’s life journey, decisions, successes, and failures will be recorded and archived for possible future study (Emeagwali, 2006). Effectively, human beings will become the bedrock of the interlinked world, seamlessly linked to central hubs and repositories. When this happens, desktop and laptop computers will become obsolete and disappear into the Internet (as is happening in cloud computing), and fifty years later, the Internet will also become obsolete and disappear into humanity. After that transference into humanity, the only aspects that will remain are the nodes, which are actually people, and they will be forever connected in order to work together" (pp. 35-36).

References

Emeagwali, Philip. “Intellectual Capita, Not Money, Alleviates Poverty.” Daily Motion, 2008. http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x45yrw_intellectual-capital-not-money-alle_news#.UQX9rUo4I4k (accessed January 2013).

---. “The Internet as an Emerging Global SuperBrain.” Emeagwali, http://emeagwali.com/essays/technology/weather/computing-the-weather.html (accessed June 1, 2010).

Notes on J. Lave and Situated Learning Communities

Situated Learning Perspective, Ecological Theory for Learning, Networks, & Situating Learning Communities of Practice – (Barab, Lave) Barab, S. and M.W. Roth. (2006). “Curriculum-Based Ecosystems: Supporting Knowing from an Ecological Perspective” Educational Researcher, Vo. 35, No. 5, pp.3-13. June/July.

Lave, J. (1991). Situating learning in communities of practice. In L. Resnick & S. Teasley (Eds.), Perspectives on socially shared cognition (pp. 63-82). Washington, DC: APA.

Summary of Situated Learning Perspective, Ecology Theory for Learning, Networks, and Communities of Practice:

Barab and Roth’s analysis of networks situates the environment at the center of learning. The authors demonstrate “the role of the environment in distributing cognition” (pg. 6). They breakdown the simplistic idea of applied knowledge by deconstructing networks with discussions about the ways in which agents (or learners) engage and participate within the environment; the tools they use, how resourceful they are with the tools, the ways in which agents “wax and wane” (pg. 5) within a particular network depending upon targeted goals and understanding. The network, the authors argue, “is bounded by its function” (pg. 6). That is, how agents participate and contribute to the network itself determines its overall function. The authors believe in participation over acquisition. They state, “[i]ntegrating this theoretical conviction into our argument suggests that knowledge acquisition may be overrated and that a more important role of education is to stimulate meaningful participation” (pg. 6).

Jean Lave, a social anthropologist, puts a social (and to some extent, a human) face on cognitive science. Her article on situated learning asks us to rethink the idea of learning as a “emerging property of whole persons’ legitimate peripheral participation in communities of practice.” She asks the question “why is learning problematic in the modern world?” and briefly outlines a historical perspective of Marxist social theory to explain 1) alienated conditions of contemporary life, and 2) how commoditize labor diminishes possibilities for “sustained development of identities and mastery” (pg. 65). From the onset, we understand Lave takes a social and cultural approach to cognitive science. As such, she critiques two genres of situated activity theory by introducing the theory of situative learning. The first, Cognition Plus View (CPV) locates situatedness in the individual, internal business of cognitive processing, representations, memory and problem solving, and cognitive theory. (This view has a fixed Cartesian view of the world). The second, Interpretive View (IV) locates situatedness in the use of language and/or social interaction. Meaning is negotiated [and] the use of language is a social activity rather than a matter of individual transmission of information, and situated cognition is always interest-relative. Unlike CPV and IV above, situated learning, according to Lave, “claims that learning, thinking, and knowing are relations among people engaged in activity in, with, and arising from the socially and culturally structured world” (pg. 67).

Lave discusses Jordan's 1989 ethnographic research on apprenticeship in the Yucatec Mayan Midwifery community (pg. 68). The apprentices in this community are peripheral participants, legitimate participants, and legitimately peripheral to the practice of midwifery. Community members of Yucatec Mayan Midwifery have access to broad knowledgeability of the practice of midwifery and to increasing participation in that practice (pg. 70). With this example, Lave argues against prior notions that teaching resources (in the Western sense) are necessary in order for effective apprenticeship. Though this community is impoverished, and despite a lack of identifiable teaching resources, Jordan’s ethnography shows that “learning activity is improvised” (pg. 7) and knowledgeability and an ongoing transfer of newcomers to oldtimes are established in this particular community. Lave’s discussion of Alcoholics Anonymous is also an example of a community of practice where newcomers gradually develop identities as nondrinking alcoholics—i.e. learning as legitimate peripheral participation (pg. 71). Both examples Lave mentions resonates with Jenkins' (2006) notion of affinity spaces (pg. 9) in a participatory culture, that is, spaces where informal learning communities acquire skills and knowledge through apprenticeship. These spaces, according to Jenkins, are powerful sites of generative learning where “aesthetic experiments and innovations emerge” (pg. 9).

Though Lave initially presents a “seamless whole” (pg. 74) of communities of practice, she also acknowledges that continuity and displacement (of oldtimers) are necessary for someone to become a full practitioner in a community of practice—a complex and muddy reality.

The crux of Lave’s article comes toward the end with further analysis on what Henning (2004) discusses of Lave as the commoditization of knowledge. That is, the commoditization of knowledge and learning results in the anthropomorphizing and objectification of people (Lave, 1991). People become products within an exchange system of learning (pg. 75). As a result, the learner, or agent “has little possibility of fashioning an identity that implies mastery [since] commodification of labor implies the detachment of the value of labor from the person” (pg. 76). In other words, personal identity, a significant factor in knowledgeability according to Lave “devolves elsewhere” or is lost.

Lave’s 1991 article as well as her work mentioned in Henning’s 2004 article, "Everyday Cognition and Situated Learning", establishes nicely the ways in which Lave puts a human face on cognitive science.